Veterinary Care Inequities

I recently researched and wrote a lengthy article for veterinary professionals on veterinary care inequities. It’s NOT YET published, but some important parts got axed in editing. It felt like an issue of fragility, if you understand that term. I argued (and lost). I feel that NOT sharing painful details about the problem only perpetuates inequities many people face when trying to access veterinary care for their pets. So, I alerted some of the people I interviewed about the editing cuts and got permission to share these key points here instead. Who isn’t getting the veterinary care? How common are veterinary care inequities? What barriers do people face? What underlying biases preserve the problem? And, how does this bias and lack of access feel in real life? Let’s take a look.

Look for places I’ve marked as being edited out of my article on this topic. I included some of the rest for context.

Veterinary Care Inequities

Who isn’t getting veterinary care?

The short answer is that the largest subset of pet lovers who don’t have adequate or easy access to veterinary care are those formerly referred to as “the working poor.” Michael Blackwell, DVM, MPH, FNAP, who chairs the Access to Veterinary Care Coalition, explained to me that the current term is ALICE, meaning asset limited income constrained employed. Not slackers. Not scammers. People working VERY hard to get by.

In 2018, the coalition published Access to Veterinary Care: Barriers, Current Practices, and Public Policy with a deep dive into the data and thoughtful consideration of the many elements the contribute to veterinary care inequities.

The report includes information about the sources of these pets in ALICE families, and in many cases, pets get taken in as strays and from friends and family members also struggling with low incomes, food and shelter insecurities, and medical issues. In other words, people with the least to spare generously open their homes to pets, which as Blackwell explained to me should be something we want in the world. It’s important to understand that many of those facing veterinary care inequities get in over their heads, but NOT because they actively purchase or adopt pets through typical channels.

How common are veterinary care inequities?

Estimates based on inhouse data from PetSmart Charities peg the number of pets without adequate veterinary care top 50 million. That 2018 access report estimates that 29 million dogs and cats live with families enrolled in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which is just one indicator of need.

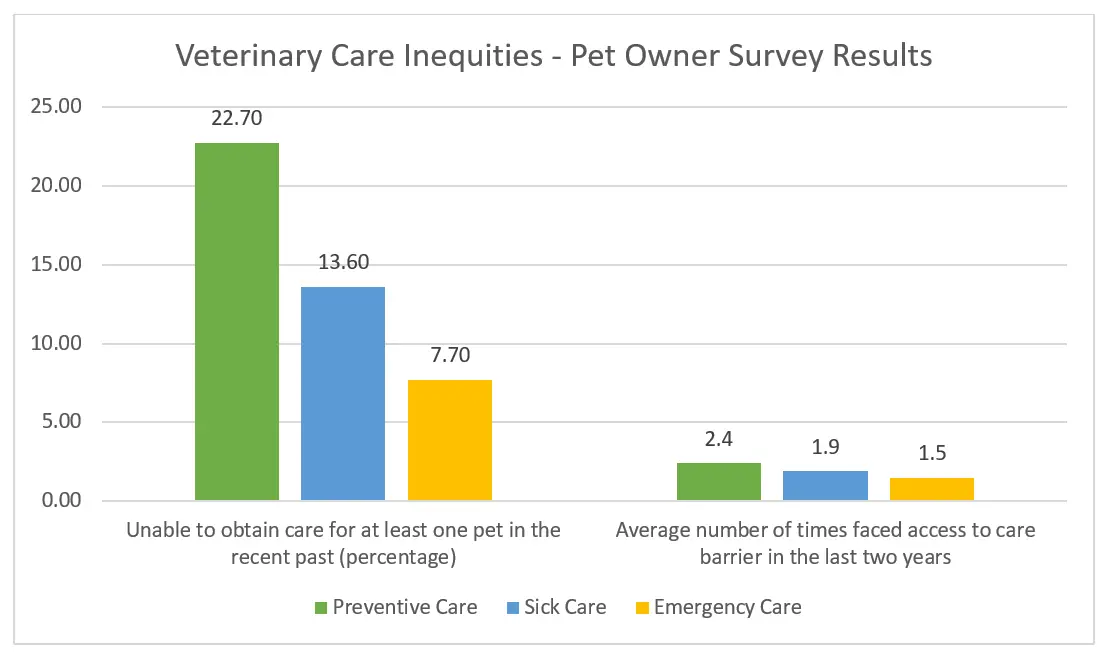

Pet owner surveys found that:

- 22.7% couldn’t access preventive care

- 13.6% couldn’t access sick pet scare

- 7.7% couldn’t access emergency veterinary care

In addition, this happened more than once to families in 2 years:

- Preventive care – 2.4 times

- Sick pet care – 1.9 times

- Emergency veterinary care – 1.5 times

What barriers do people face?

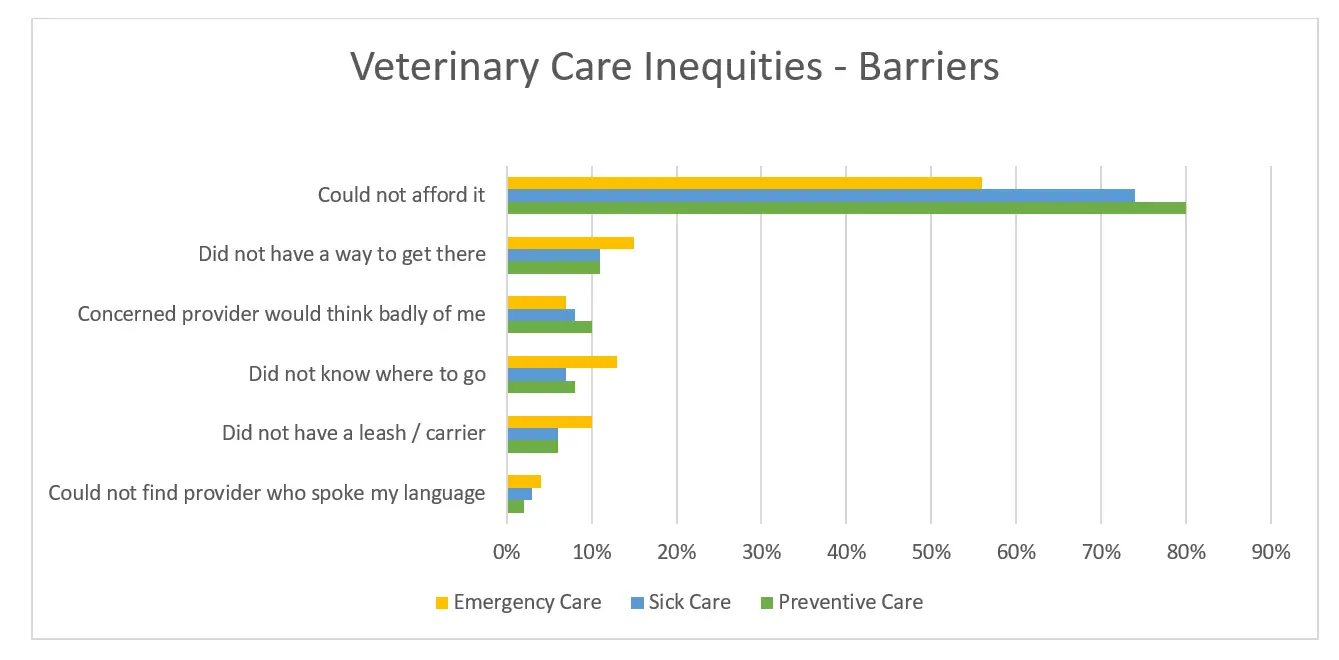

By far, financial issues pose the greatest barrier to pets getting the veterinary care they need. The full list includes these reasons people face barriers and veterinary care inequities:

- Could not afford it

- Did not have a way to get there

- Concerned provider would think badly of me

- Did not know where to go

- Did not have a leash / carrier

- Could not find provider who spoke my language

[This next section includes information cut from my article.]

Veterinary Care Inequities

What underlying biases preserve the problem?

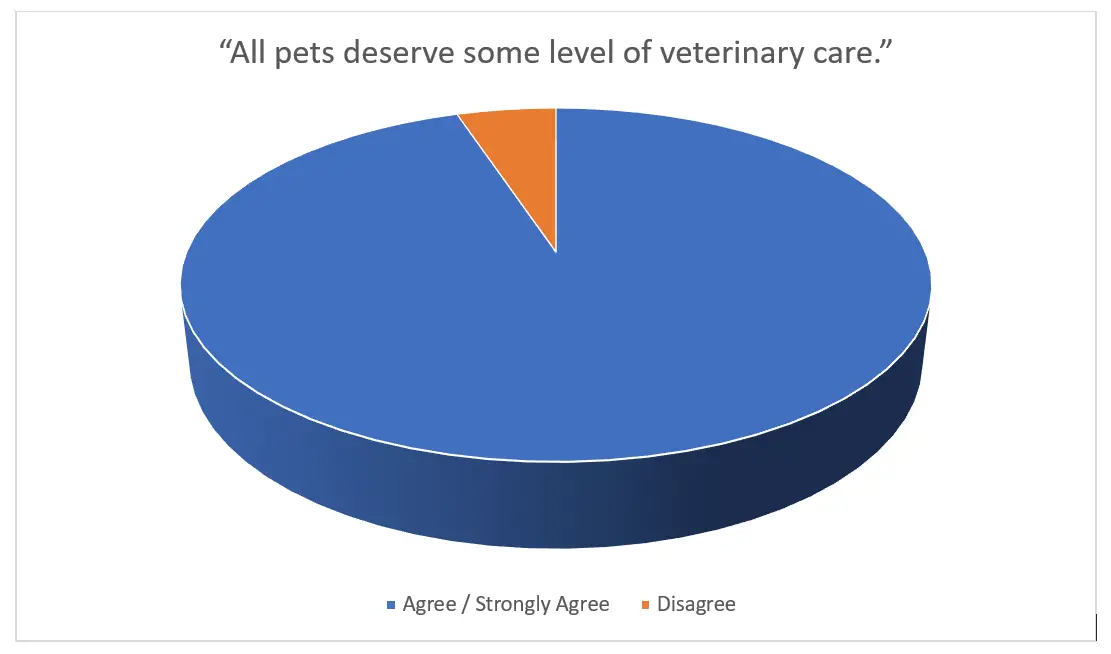

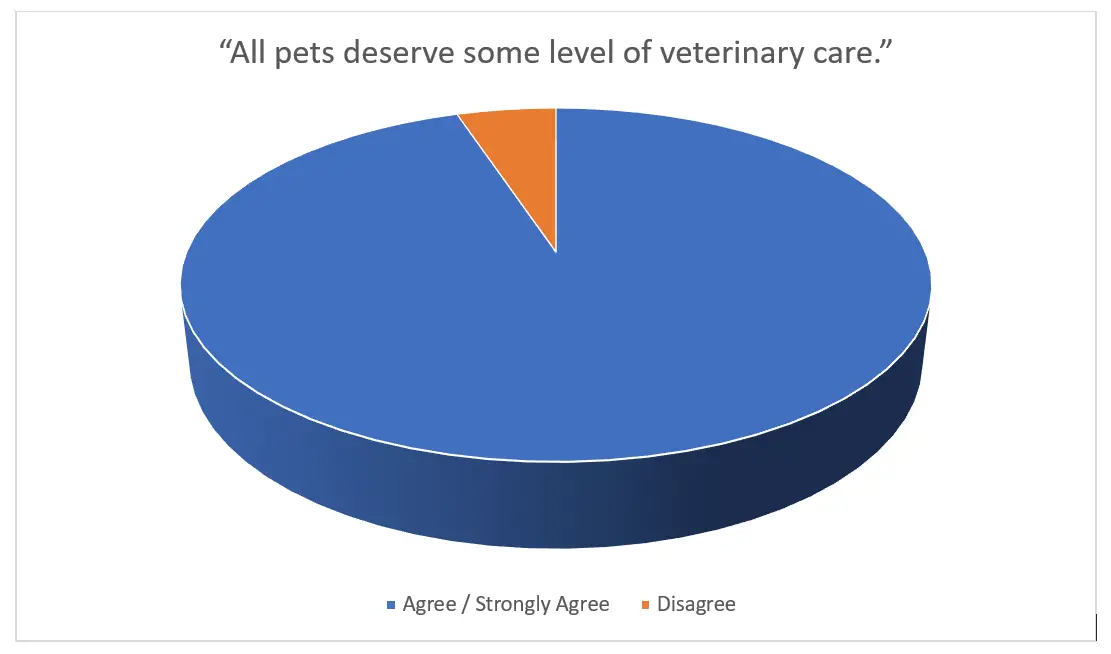

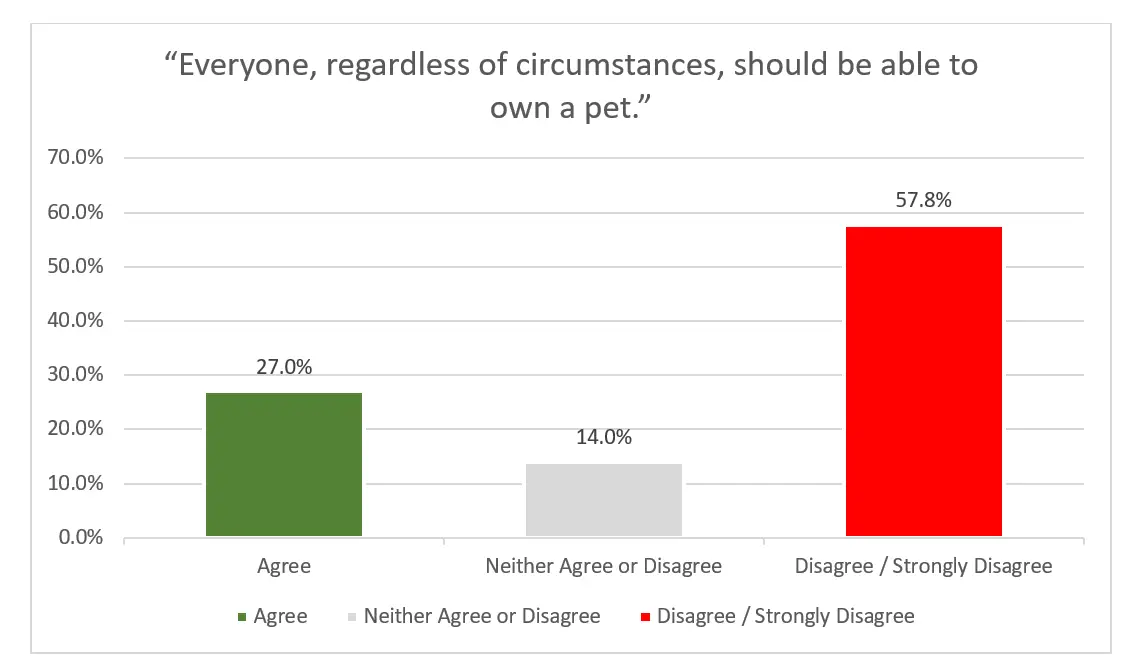

The veterinary access report included a survey for veterinarians. Among other things, it measured consensus with statements about rights and responsibilities around pet ownership. While 94.9 percent either agreed or strongly agreed with “All pets deserve some level of veterinary care,” consensus fell dramatically for the statement “Everyone, regardless of circumstances, should be able to own a pet.”

- Only 27 percent agreed

- About 14 percent neither agreed nor disagreed

- 57.8 percent disagreed (23.9 percent strongly disagreed), saying things in focus groups like “pets are not a right.”

You hear / see these same sentiments on social media and conversations around people struggling to afford veterinary care or facing other barriers, including transportation issues since public transit and even driver apps are NOT friendly to passengers with pets and even something as simple as not having collars, harnesses, leashes, or carriers to safely transport pets.

I follow a veterinary technician, also a comedian, who makes jokes about the kinds of makeshift carriers people show up with at veterinary hospitals. He even sells t-shirts about it. Now that I know more, I find it less funny.

Robyn Jaynes, DVM, director of veterinary affairs, PetSmart Charities, told me in an interview about how veterinary teams really need to learn to suspend judgement, including for people showing up with a cat in a pillow case. Remember, from above, “Concerned provider would think badly of me,” showed up on the barriers list.

***

[This next section includes information cut from my article.]

Veterinary Care Inequities

How does this bias and lack of access feel in real life?

Often drawing on firsthand experience, Bobbi Dempsey writes about issues related to poverty and income inequality. She recalls living with a few pets in childhood, mostly cats, but dozens of moves made keeping them impossible.

Dempsey recognizes others’ judgements “that imply poor people who can’t afford vet care, just don’t care, are kind of oblivious, or unfeeling towards their pets, and it’s usually just the opposite.”

A few years ago, Dempsey’s late mother received a handwritten letter from a veterinary practice that Dempsey describes as “scolding” about overdue wellness services, including something to the effect of “If it’s not that important to you for your dog to come in, then maybe we’re not the right vet for you.”

That letter landed hard. Her mom lived in poverty, had just lost her husband, and was “literally taking up a collection to bury him,” Dempsey says.

Where Dempsey lives in rural northeastern Pennsylvania with high poverty rates help isn’t readily available. Just as food deserts exist in communities without grocery stores, people also experience veterinary deserts, where care options are limited or non-existent.

“I think a lot of people, especially from bigger areas, assume that there are all these rescues and charity organizations that help,” Dempsey says.

***

Veterinary Care Inequities

Possible solutions?

Later this year (2022), I look forward to reading the AlignCare pilot program report from Blackwell’s Program for Pet Health Equity at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, to see how their program worked in various in test cities. Maybe I can write more about this issue when that report comes out.

There’s also a new hospital not far from me in Colorado — Dumb Friends League Veterinary Hospital at CSU Spur — that offers $150 flat-rate diagnostics and flat-rate treatment plans, without people having to prove need, which the league feels is another barrier.

Notice I’m not telling you about how big donors or foundations or other financial solutions afoot. That’s because according to the folks I interviewed from PetSmart Charities, it would take $20-$23 billion per year to help all the pets not receiving adequate veterinary care, and that’s not possible, even if you lumped every pet organization together.

Strong statement from the access report

The access report introduction includes this powerful statement about how big this issue really is. “Lack of access to veterinary care is a complex societal problem with multiple causes, with socioeconomic status being an important factor. Simply stated, millions of pets do not receive adequate veterinary care because the costs are beyond the family’s ability to pay. This may be the most significant animal welfare crisis affecting owned pets in the United States.”